David Winpenny, Chairman of Ripon Civic Society, looks at the life and preoccupations of a former Ripon resident whose scientific work and idiosyncratic ideas appear to have been rather at odds with each other.

At the bottom of Clotherholme Road, not far from its junction with Studley Road, is a large but reticent Victorian House with white-painted gateposts with the name ‘Clova’. Today it is the Clova House Care Home, and has been much extended, but at the end of the 19th century it was home to one of the most interesting and eccentric people who ever made their home in the city.

Charles Piazzi Smyth was one of the most eminent scientists of the 19th century. His father was a naval officer based in Naples when he was born, and the baby was named after a renowned Sicilian astronomer, Giuseppe Piazzi. Educated at Bedford Grammar School, he was given an apprenticeship at the Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope – he was there in 1836 when Halley’s Comet appeared. Young Piazzi was a bright young man and in 1845, aged just 26, he was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland and Professor of Practical Astronomy at Edinburgh University. He stayed for 43 years, undertaking some important scientific work in spectroscopy and meteorology.

He instigated the one o’clock gun that is still fired every day at Edinburgh Castle, and the red time-ball that falls on the Nelson Monument on Calton Hill at the same time; the aim was to give an accurate time signal to the fleet when it was in Leith Harbour. He was the first person to use a telescope on a mountain top – on Alta Vista on Tenerife in 1856. As a pioneer of photography perfected a new type of high-quality miniature image, only an inch square, which could be enlarged without loss of quality.

All this was good, solid stuff. But Piazzi Smyth had a dottier side; he was obsessed by Egypt’s Great Pyramid. In fact he was, as Sir Flinders Petrie said, a ‘pyramidiot’. Piazzi was convinced the Pyramid held all the secrets of the universe. Accompanied by his wife Jessie (whom he had also dragged up the mountain in Tenerife), he measured every inch, and studied every angle. He ‘discovered’ that it was constructed on the ‘pyramid inch’ measure – only 0.001 per cent away from the imperial inch (he hated metric measurements). He ‘proved’ that the relationship of the Pyramid’s height to twice its base is equivalent to pi, and that one pound’s weight of the Pyramid is the same as five cubic pyramid inches of the earth’s mean density.

He also took the first photographs – his miniature images – in the chambers of the Great Pyramid, using coils of magnesium wire to create a bright light. Among the pictures that Smyth took is one of Jessie in the King’s Chamber, dressed in voluminous tartan skirts and looking intently into the so-called Coffer which may once have held a Pharaoh.

But Smyth’s book about his pyramidology, Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid, was largely ridiculed by his contemporaries. He was snubbed when he submitted a paper on the subject to the Royal Society and as a result he resigned his Fellowship. In August 1888, he left the Royal Scottish Observatory for the last time, and retired to Ripon – probably so that Jessie, who was unwell, could benefit from the mild climate in the lee of the Pennines, but also because nearby York gave easy access to both London and Edinburgh. Another advantage was that York was the base of Smyth’s favourite scientific instrument maker, Thomas Cooke.

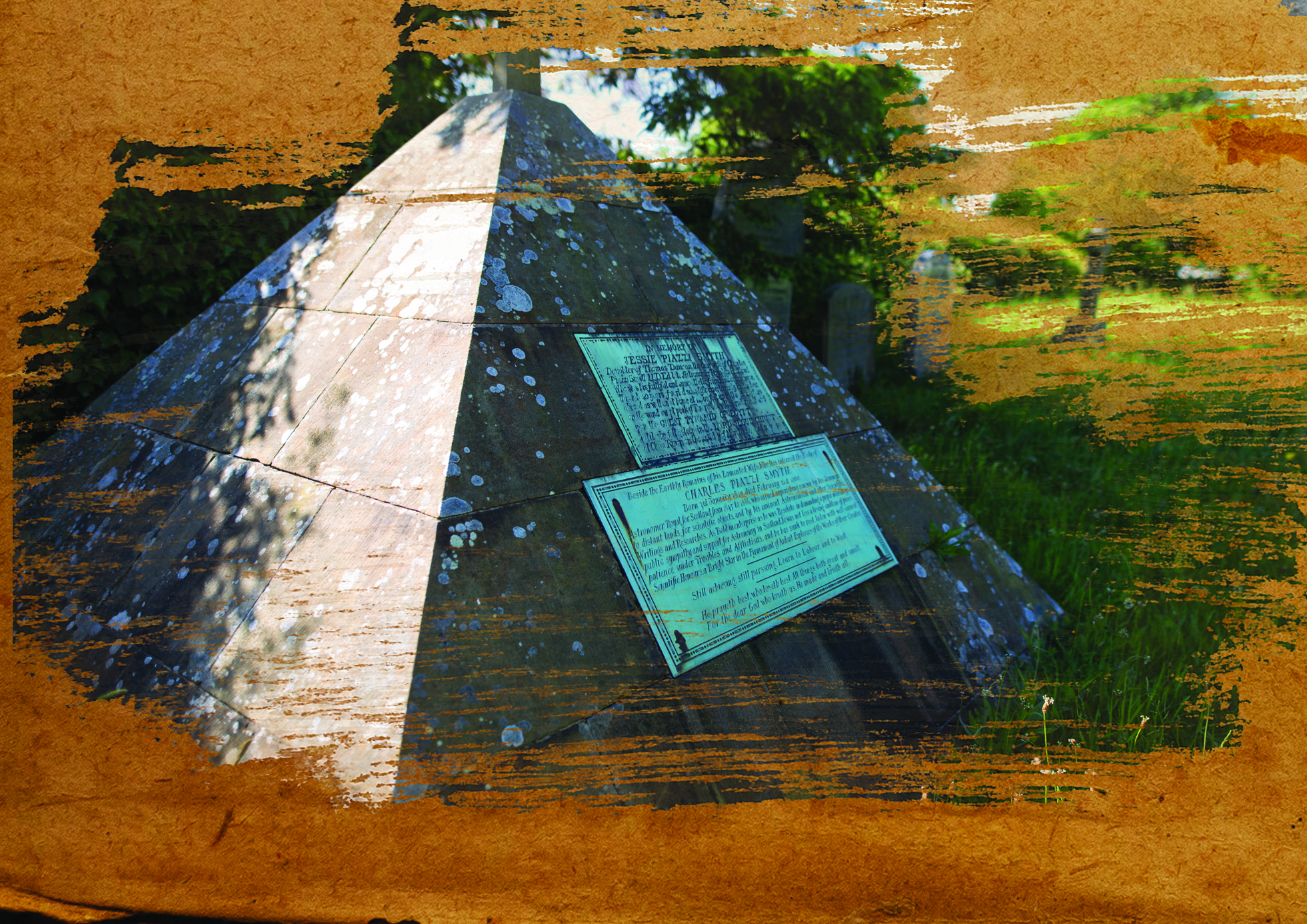

When Jessie died in 1896 Piazzi designed the pyramid-shaped tombstone topped with a cross that is now Sharow churchyard’s most unusual sight. Four years later he was buried there, too. His inscription calls him ‘a Bright Star in the Firmament of Ardent Explorers of the Works of their Creator’.